“City Architexture” and Culture of Remembrance

From November 2022 to March 2023, students of two Croatian grammar schools, I. Gimnazija Varaždin and XV. Gimnazija Zagreb participated in a history project entitled “City Architexture” focusing on the culture of remembrance. Through research about different architectural structures from the 20th century, the students learned how political propaganda influences citizens’ perception of historical monuments and buildings

Culture of remembrance

Culture of remembrance refers to the social and cultural practices that help to preserve the memory of significant historical events or people, particularly those that are traumatic or difficult to reconcile with. This can include the commemoration of war, genocide, and other atrocities, as well as the celebration of cultural and intellectual heritage. The aim of a culture of remembrance should be to foster empathy, understanding, and reconciliation, and to prevent the recurrence of past injustices.

“City Architexture” – two Croatian grammar schools’ project

The aim of the project “City Architexture” was to encourage Croatian high school students to explore the phenomenon of the culture of remembrence, through independent and group research of several public buildings, monuments and public spaces in Zagreb, a capital of Croatia and Varaždin, a town in the north-west region of Croatia. Under the guidance of two history teachers, Marko Žganec from Varaždin and Danijel Mrvelj from Zagreb, the students from 2 grammar schools firstly conducted research and prepared presentations, which was followed by two field trips, the first one taking place in November in Zagreb and the second one in February in Varaždin. The project was rounded-off with final group discussions in March. Eight students from XV. gimnazija Zagreb analyzed one of the most famous city squares, Trg žrtava fašizma, where one of the most controversial public buildings is situated, popularly called Džamija (the Mosque), while the students from I. gimnazija Varaždin explored the famous Synagogue and 2 prominent city squares with their monuments. Since in the 20th century Croatia changed several regimes and was a part of several different states, the students learned quite a lot about how collective memory of the two urban communities changed under political influences.

The controversial “Džamija” and “Trg žrtava fašizma” in Zagreb

During the field trip in Zagreb, the 8 students of XV. gimnazija Zagreb, together with their teacher Danijel Mrvelj firstly, presented the results of their research to their colleagues from Varaždin after which all the students visited the two researched public spaces: Trg žrtava fašizma (The Square of the Victims of Fascism) and Dom hrvatskih likovnih umjetnika (Home of Croatian Artists), popularly called Džamija (The Mosque), where they were given a guided tour and learned even more about that famous exhibition hall.

One of the most controversial Zagreb’s squares changed its name seven times in 100 years and today it is called Trg žrtava fašizma (The Square of the Victims of Fascism). When it was first designed in 1923, the squre was ambitously planned to be a place of new urban environment where a new society and modern luxury buildings would be constructed. At that time the square was called Trg N (Square N ). In 1927, the name of the square was changed to Trg Petra I. osloboditelja (the Square of Peter I the Liberator ), after the first king of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (1918 – 1921). When the WW II started, for a short period of time (1941 – 1942), the square was known just as Trg III (Square III). In 1942, the name was, yet again, changed to Trg bana Kulina (the Square of Ban Kulin) after an important historical Bosnian leader, Kulin, in order to emphasise the connections between Croatia and Bosnia, which was important to the Ustasha regime. In 1946, during socialist Yugoslavia, the square became the Square of the Victims of Fascism (Trg žrtava fašizma) because the communist regime of SFR Yugoslavia wanted to stress and perpetuate the antifascist ideology. In 1990, just a year before the Croatian War of Independence) would begin, the name of the square was changed to Trg hrvatskih velikana (the Square of Great Croats), which was kept for a decade when Croatian nationalism was at its highest point. In 2001 it was changed to Trg žrtava fašizma (the Square of the Victims of Fascism) – the name which it holds to this day.

This famous square is dominated by an impressive round exhibition hall, called Dom hrvatskih likovnih umjetnika (the Home of Croatian Artists), an impressive architectural masterpiece, designed by a famous sculptor Ivan Meštrović. It changed its name and purpose 5 times since its construction in 1938. When it was first constructed it had a double function. It was a memorial dedicated to King Petar I of Yugoslavia and at the same time an exhibition hall and its name was Dom hrvatskih likovnih umjetnika (The Home of Croatian Artists), which meant it had an educational and artistic purpose. After the change of the regime in 1941, its purpose was changed and in 1944 it became a place of worship for the Muslim population in Croatia. During that period, the building was known as Džamija (the Mosque), to which 3 minarets were added for its religious purposes. Considering that Ante Pavelić, the fascist leader of the Indendependent State of Croatia, thought that the people of Bosnia, who are largely muslim, were politically important, it makes sense why during his regime the building would become a mosque – a place of worship for Muslims living in Croatia. When the Communist Party took over in 1945, the three minarets were pulled down and in 1955 the building became Muzej revolucije naroda Hrvatske (the Museum of Revolution), in order to commemorate the communists and partisans achievements during the WW II. In 1991 when Croatia gained its independence and became a democratic state, the museum regained its original purpose and it became Dom hrvatskog društva likovnih umjetnika (The Home of Croatian Society of Artists) where even today various exhibitions are held. To summarize, during the 20th century, the Croatian state was a part of several countries and the building changed its purpose each time a new regime took place. It is interesting to note that although the building served as a mosque for only a year, even nowadays the citizens of Zagreb usually call it “Džamija” (the Mosque) because it was culturally and politcally its most outstanding role in the 20th century.

The Synagogue and forgotten monuments in Varaždin

In Varaždin the students of Prva gimnazija Varaždin presented their research to their colleagues from Zagreb. There were three different groups presenting three different public spaces. The first group talked about Spomenik Velikom ratu (the Memorial to the Great War) which used to be on Franjevački trg (the Franciscan Square). The second group presented what they learned about the forgotten statue of the King Aleksandar Karađorđević, which used to be on the main city square, popularly called Korzo. Finally, the third group discussed a turbulent history of the Synagogue in Varaždin. After the presentations, all the students visited the two most important squares of Varaždin and the newly reconstructed synagogue. So what did they learn about forgotten and remembered public spaces in Varaždin?

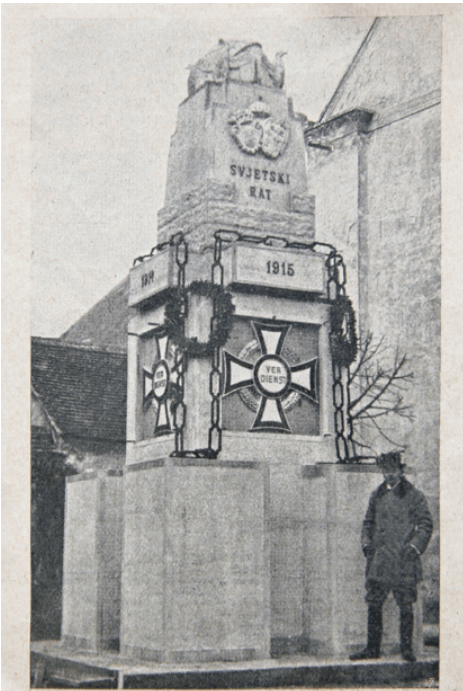

The Franciscan Square first hosted Spomenik Velikom ratu (the Memorial to the Great War), which was constructed in 1915 in order to commemorate the victims of the war. In addition, it had a charity purpose – the citizens could buy nails there and the collected money was given to widows and orphans. After the collapse of Austrian-Hungarian Empire, the monument was regarded as politically incorrect and it was pulled down. In 1931 the statue Grgur Ninski, (Gregory of Nin) replaced the Memorial to the Great War. Grgur Ninski was a medieval bishop of the Croatian city of Nin, who is known for strongly opposing the pope and the official circles of the Church. The act of putting up the Grgur Ninski Monument reflected the political emphasis on slavic identity and unity of the Kingdom Of Yugoslavia. Since Grgur Ninski is also regarded as an important figure in Croatian history, the Monument managed to survive all the changes of the states and regimes throughout the 2oth century.

What the students also discovered through their research is that most citizens of Varaždin don’t even know that there used to be the statue of the king Aleksandar Karađorđević in Varaždin. The monument was built with the support of the citizens of Varaždin in order to commemorate Yugoslavian King Alexander after he had died in 1934. It was destroyed on the second day after the establishment of NDH in 1941, because Alexander Karađorđevića was Serbian and he represented the Serbian authority over Croatia and its people, which was unacceptable for the nationalistic Ustashe regime. In destroying the monument, the Ustashe regime neglected the fact that there were some other historically valuable features connected with events in Croatian history on it.

Lastly, the third group of the students discussed Varaždin’s Synagogue and the Jewish population in Varaždin during the Second World War. The first, smaller synagogue was built in 1812. However in 1861 a larger synagogue was constructed on a different location. Then during the Second World War, when the Independent State of Croatia was a part of the Axis powers, the persecution of the Jewish began. Varaždin quickly became the first city in Croatia without any Jews, and the Synagogue became a theater / cinema. Later it was used as a storehouse for food and weapons and as a military prison. This function further undermined the Jewish identity because many were detained and tortured in their own synagogue. In 1969, during SFRY, the Synagogue became a National Educational Centre and a cinema hall. During the 1990s, the building was neglected and started to fall apart. However, in the late 1990s / early 2000s, the reconstruction of the building began and today it is restored as a synagogue in order to commemorate the disappeared Jewish community and cultural heritage, despite the fact that there are almost no Jewish people in Varaždin.

Conclusion

By doing research and visiting the public spaces, ghe students gained a new perspective on just how powerful propaganda can be, to the point it impacts whole generations of a nation. Most people living in Varaždin don’t even know that there used to be a statue of the king of the First Yugoslavia and they don’t ever question why there’s a monument for Grgur Ninski – they wouldn’t even notice if it got took down tomorrow.

“After participating in this project, I realised that the culture of remembrance is all around us”, said a student of Prva gimnazija Varaždin, Lovro Pirović. “I believe that the fact it’s rarely ever talked about is sort of a problem… people aren’t aware of that.”

Another student from Varaždin, Ivan Benčik, said: “I’m glad I had the opportunity to take part in this assignment. I’ve learned a lot of information you don’t get taught in history classes. I especially enjoyed the debates. It was very productive and intellectually stimulating.”

As history professor Žganec said, “History as such is abstract, it does not discriminate, it does not care about emotions and what is important to a particular community. Its role is only to inform, bring facts, and describe them. In this project, we ‘oppose’ this ‘heartless’ history by seeking the community’s standpoint, something that reflects identity, we seek ‘breaks’ within, specifically in this case, the interwar period, why they happen and how the community that is directly ‘affected’ by them reacts.

Written by Katarina Bukovec, Prva gimnazija Varaždin, Croatia